Mommy, How Do You Read?

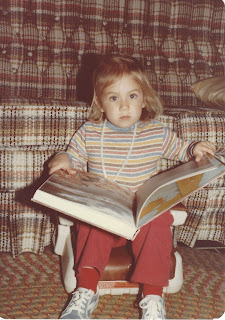

One long-ago day, when I was reading to my little girl, she looked at me and asked, “Mommy, how do you read?” I had no answer.

Reading came as natural as breathing to me. On the first day of first grade, my teacher put two words on the board and said, “This says the and this says cat.” From that moment on, I could read. From listening to my classmates, I knew that reading didn’t come so easily for everyone.

Many children struggle to learn to read. Research identifies several factors that put children at risk for reading failure: poverty, language barriers, parents’ reading skills and attitudes, word-processing difficulties, as well as biological and psychological learning deficits. Literacy is essential to success affecting health, safety, self-respect, cultural development, career advancement, and academic achievement.

Studies show that children who are late to read fall behind as their schooling continues putting them at risk for frustration and failure. Early readers read more, learn more words, gather more information, and attempt more complex learning tasks. Reading is complicated. Key factors that influence reading development include phonemic awareness, decoding, automaticity, vocabulary acquisition, comprehension, extensive reading, and motivation.

Phonemic awareness is the ability to identify the small units of sound (phonemes) which make up words and how these can be segmented (pulled apart), blended (put together), and manipulated (added, deleted, and substituted). Phonemic skills, generally the first children acquire, include rhyming, alliteration, and counting syllables.

Decoding, or phonics, is the process of converting the printed word into its corresponding sounds or sounding out a word. Readers must connect symbol (the letter) to sound (phonemes). Many children sing the alphabet but can’t connect the letters with their corresponding sounds.

Automaticity is the ability to quickly and effortlessly recognize words leaving the reader’s mind free to gain meaning from text. Proficient readers don’t stop to decode every word. Automaticity affects the smoothness and expression necessary for comprehension.

Proficient readers gain vocabulary at a greater pace giving them another advantage for understanding texts. Children who are read to and have a wide range of experiences build “word-banks” they can draw from when encountering new words and concepts in texts.

Comprehension grows as readers master decoding, gain automaticity, bank vocabulary, and connect concept to print. Reading often and with varied texts and purposes builds vocabulary and comprehension skills.

Motivation is both the hardest and easiest skill of reading. Any new skill takes effort. Readers must have a purpose and a desire to read. Reading must be enlightening, instructional, exciting, and practical. Most importantly, reading must be fun.

Long ago, I had no answer as to “how” I read but I sure knew that I loved reading. The first step to starting children on the road to reading success is reading with a parent. My daughter reads to her children now. They’ve started their journey to reading success. Grab a book and start your children now. (This is the first in a series about reading success.)