The Nonnas

We kids considered it paradise.

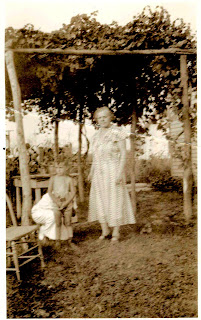

All six houses on our dead-end street were filled to the brim with at least three generations. Kids spilled out every morning, grabbed their friends, and headed to the pier to fish or crab or to reenact epic dramas on the rocks along the bay. In the afternoon’s heat, our parents swam with us at the bay beach or loaded us into cars, and the whole neighborhood headed to the ocean beach. In the evenings, we gathered around a huge table under a grape arbor to feast on pasta, fresh veggies from the garden, and “frutti del mare,” the clams, crabs, snails, and fish caught each day. As the sun set, we gathered around a wood-fire in a rickety old grill, swatting mosquitoes, as the little ones fell asleep in their parents’ arms and the big kids skittered about while grandparents warned us to watch out for the fire.

“Paisans,” related by our common heritage, the grandparents, and some of our parents often slipping into Italian, we laughed at generations of funny stories, cried over lost but never forgotten loved ones, sang sentimental songs, and cooed over every baby joining our family. Holding this huge family together were the “Nonnas,” our grandmothers.

The grandfathers arrived every Thursday night and left on Sunday afternoons. Our parents cycled in and out as work schedules allowed. The Nonnas stayed all summer to cook, clean, and care for their children and grandchildren. They tended the garden, cleaned the crabs, clams, and fish, cooked the pasta, washed mountains of dishes, changed diapers, washed faces, swept porches and steps, haggled with vendors selling produce from the backs of trucks, bandaged fingers cut by fishhooks, scrubbed and wrung out mountains of clothes and sheets, hung them out to flutter over the backyards, told stories, and hugged everyone. We kids didn’t realize how much love was wrapped up in our Nonnas hard work. We all helped out a bit but our paradise rested on the labor of our Nonnas who loved us so.

After we were settled into bed, the Nonnas dropped exhausted into lawn chairs around the fire to share stories of their grandchildren, their worries and hopes, their sorrows and joys. Now we are the grandparents. When our grandchildren visit, we are sometimes exhausted, but we wrap our love around our grandchildren and remember the Nonnas who loved us so.

Paradise returns.