Patchogue Mornings

Capacity 12

52 on Weekends

Once in a while, when walking through the yard on a cool summer morning, I get a whiff of paradise. A cool breeze, the scent of fresh basil, or the call of a mourning dove, and I am there.

In the early days of the last century, my great-grandparents bought a summer bungalow on a dead-end street a block and a half from the Great South Bay in Long Island. The family took the train from Brooklyn then hired a horse and wagon to travel the last few miles. A sign hung over the front door — Capacity 12 — 52 on weekends. I imagine their excitement as they came in sight of the bay — the same excitement I felt whenever we did the same.

It was a small house with just a dining room, kitchen, and two small bedrooms downstairs but the glories of the house included a screened front porch and an open attic accessed by a steep staircase. I imagine my great-uncles and aunts arguing about who would get to sleep in the attic just like we did.

Huge trees hugged the attic’s windows and every breeze blew a scent of the bay into our dreams. Arising early, we trooped downstairs in our pajamas and out onto the airy porch. Six houses snuggled close on our block. We called to our friends on their porches, “What are we doing today? Are we going fishing? What time are we heading to the beach?” Always “we,” never “you” or “I.” We were one family.

After breakfast, we wiggled into our bathing suits and tumbled down the back steps into our shared backyard. A dozen children, many of them cousins, might be waiting for us. We mixed and matched age groups as we grabbed our fishing poles and headed for the pier. We chattered as we set our lines, “Remember when the snappers were running? Remember the eel in the crab cage? Uncle Joe ate it!”

Afternoons, the whole neighborhood headed to the beach. The older kids jumped right into the bay. Toddlers splashed in a wading pool filled with salt water pumped from the bay. Some days, we loaded up the station wagons and drove to the ocean beach. Hauling lunches, playpens, and blankets, we struggled over the dunes onto the beach. While the adults played cards or gabbed and watched the little kids play in the sand, we leaped over the ocean waves — always accompanied by a parent or aunt or uncle to keep us safe.

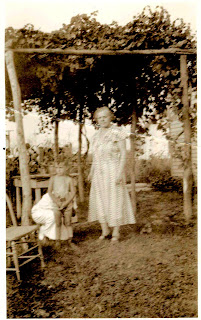

Later, as we showered under a backyard hose, the Nonnas cooked dinner fresh from the garden flanking the backyard. We ate under the grape arbor at a table that sat 12, or 15, or as many as wanted to join us. After dinner, the Nonnos played a card game fueled by rivalries going back to Italy. “Due!” they’d shout as they slapped down a card followed by raucous laughter. After dark, our friends and families, young and old, gathered around a fire — a circle of light and family.

Four generations enjoyed that bungalow before it was taken from us by a not-so-friendly fire. Our memories and friendships survive. The generations live on. Paradise lives inside us ready to awaken any summer morning.